Text: Ruth Astrid L. Sæter

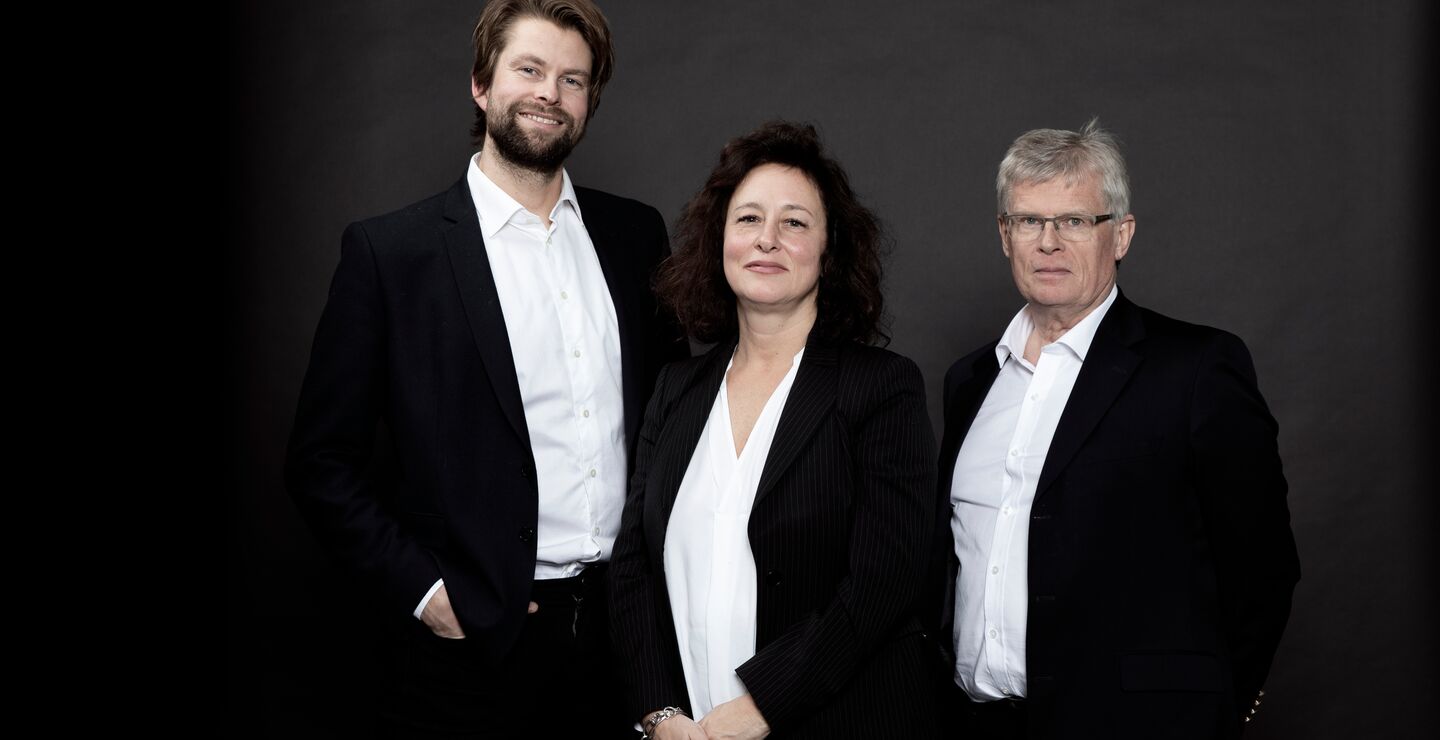

Photo: Torbjørn Brovold

During a couple of morning lessons, three of BI’s brains meet to discuss developments in leadership studies, leadership development and leadership training, from the 1970s to the present day.

These three brains are: Head of Department and Professor Øyvind Lund Martinsen and Associate Professors Per-Magnus Thompson and Donatella de Paoli. Two psychologists and one leadership and organisational developer, all three of whom possess a keen involvement and interest in leadership studies.

“And in leadership development,” emphasises Donatella de Paoli quickly as they sit down together around the table. We will return to that, but first they are tasked with defining what characterises today’s leadership ideals and theories.

Relationships and soft values

“Leadership today is more than just managing people. Today’s leaders need to operate in a digital sphere, and this requires them to know something about technology while simultaneously having to work even harder on relationships,” says Professor de Paoli as she continues: “Many of them work in open landscapes without a fixed space. It is thus even more important for leaders to create connections and cohesion, both with and between employees.”

“Yes, the relational aspects are becoming increasingly more important. We often talk about placing greater emphasis on the “soft” perspectives of modern leadership and leadership development,” agrees Per-Magnus Thompson.

“Another obvious characteristic – and one which has become more apparent during the last 20 years – is that employees are more knowledgeable than their managers,” points out Professor de Paoli.

“And obviously this is a challenge for their managers, who have been accustomed to being a sort of oracle for their employees. When that function is no longer present, it might seem as though the whole balance of power has been shaken,” says Professor Thompson.

Digital leaders

“A modern manager will understand that leadership is all about having good interactions between managers and employees. When your employees are more knowledgeable than you, it is your job to ensure that any academic decisions are made on the best possible basis and that your employees have greater latitude to engage in production,” adds Professor de Paoli.

She conducts research on how digitalisation impacts on leadership roles, and she has seen that the role of a good leader today mainly involves being a coach and teacher who supports the development of knowledge and learning. Leaders have had to climb down from their pedestals and enter the small digital screen window.

“The structure automatically becomes flatter when you operate on digital platforms. You don’t often meet your employees in person, and this requires leaders to adopt new social and communications skills. You have to learn to listen more, understand what digital silence might mean and not least interpret body language and voices in a different way,” she says.

Leadership studies

Øyvind Lund Martinsen nods in agreement about what the two others say, and adds a new perspective to their chat by saying that many organisations out there do not appear to be taking leaderships studies seriously.

“When I give lectures I always ask how many of the leaders in the audience needed to have leadership qualifications before they became leaders for the first time. With the exception of the Armed Forces, the answer is zero, and that amazes me. What I challenge them by asking why leadership is not regarded as a subject that requires qualifications, they often reply that leadership is something that they had to discover by themselves,” he says.